“We’re on the same wavelength.”

It’s a familiar cliché: we’re feeling “in tune” with one another, thinking the same thing; I’m metaphorically “picking up” what you’re proverbially “putting down”.

Loose talk with no basis in science…right?

Maybe not, at least according to a new paper in the Journal of Consumer Research.

“In A Ticket for Your Thoughts: Method for Predicting Content Recall and Sales Using Neural Similarity of Moviegoers”, researchers at Northwestern University show that the best movie trailers actually put viewers on the same wavelength. And doing so has major payoffs: the more similar those brainwaves were between viewers, the higher the ticket sales.

The idea that different brains can be “in sync” is not new. Say, for example, that you and I are both looking at a picture of a grilled cheese sandwich.

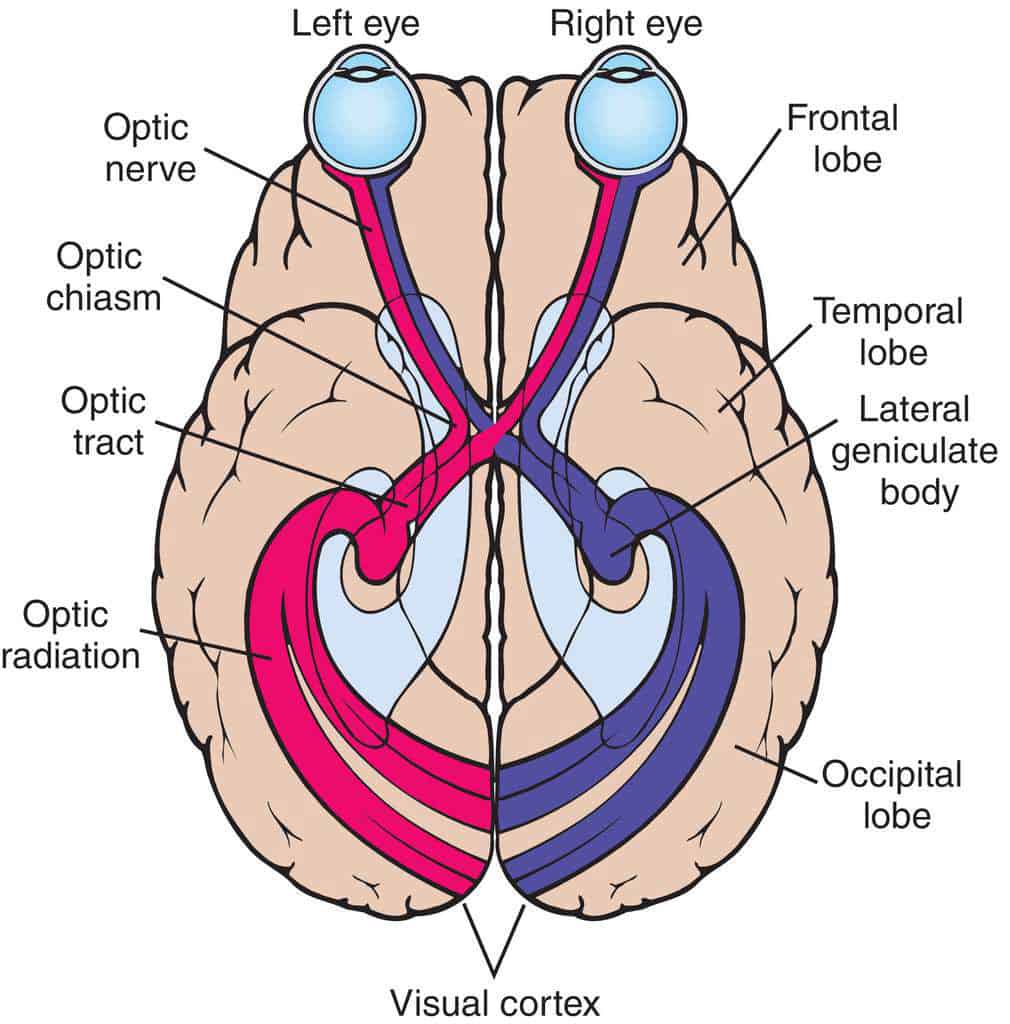

Neuroscientists have long known that visual information travels along stereotyped pathways in the brain, from the eyeballs through the optic nerves back to the early visual cortex, where the brain begins to put together the various lines, edges, and shaded regions into a coherent representation of melty goodness. Up until this point our brain activity is closely synced.

But beyond early visual areas, the similarity can quickly break down.

For example, the grilled cheese gets my hypothalamus churning out feelings of hunger, and my prefrontal cortex starts plotting out what to make for dinner. That same image triggers an episodic memory via your hippocampus of the last sandwich that gave you the stomach flu, and now your insula is reeling with disgust and discomfort.

On the other hand, when we’re both captivated by what we’re seeing — an especially dramatic scene from last week’s Game of Thrones, for example — even our higher level thoughts may be in sync. Instead of mulling over our own idiosyncratic to-do lists, we’re both marveling at how Jon Snow is going to handle the imminent knife-fight.

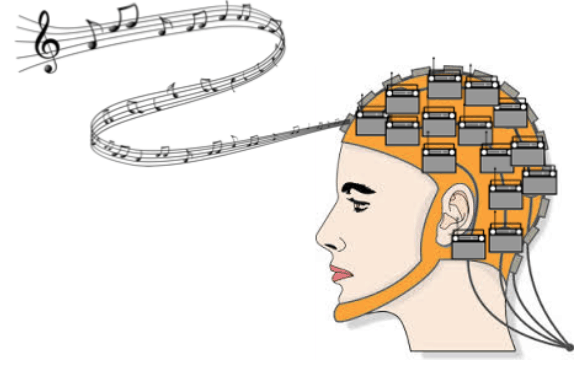

Sam Barnett and Moran Cerf, the authors of the study, found a way to measure this neural synchrony using Electroencephalography (EEG), a technology that reads brainwaves by measuring changes in electrical potential on the scalp.

Fifty-eight participants sat in a movie theater watching a feature film of their choice. Before the film started, participants donned their EEG caps and viewed several trailers from (at the time) upcoming movies — thrillers like X-men: Days of Future Past, comedies like 22 Jump Street, and animated films like Mr. Peabody and Sherman. All the while, Barnett and Cerf recorded brainwaves from 32 separate sites on the scalp, cranking out thousands of data points per second.

After the recording session, the researchers went back to the lab and started churning through the data. They wanted to know whether participants’ brains were fluctuating in unison — and whether this degree of “neural synchrony” between people might vary across trailers.

To answer this question, they calculated the Cross-Brain Correlation (or CBC).

For each trailer, Barnett and Cerf would zoom in on one electrode on one participant’s head–let’s call it Electrode 1 on Ian’s head, left side of the forehead. They’d then calculate the power (or strength of signal) in a particular frequency band for Electrode 1 at each moment of the trailer.

Did I lose you there? Don’t worry, here’s an analogy:

Think about an electrode like it’s a radio, broadcasting at any and all radio stations you might decide to tune in to.

The authors would tune Electrode 1 to a particular radio station — let’s say a station playing the latest song from a band called Alpha — and measure how strongly the signal came in while participants were watching the X-men: Days of Future Past trailer. At some moments in the trailer, the Alpha band would come in loud and clear; at other points, not so much.

Then they moved on to Patrick, and repeated this process with his Electrode 1. Again, they’d measure how well the Alpha band came through throughout the X-men: Days of Future Past trailer. Patrick would have his very own timecourse of strong and weak points.

How similar are Ian’s and Patrick’s brainwaves? The researchers simply calculated the correlation between their two timecourses. Repeating this process for all electrodes covering the scalp, all pairs of participants, and finally all trailers (yes, ladies and gentlemen, science can be tedious), we get the Cross-Brain Correlation (CBC) for that trailer.

With this data in hand, Barnett and Cerf could compare trailers based on whether they made participant’s brains react similarly. So what did they find?

Some trailers produced highly similar brainwaves across participants–the trailer for X-men: Days of Future Past leading the pack–whereas Mr. Peabody and Sherman got relatively disperse reactions. Other trailers like Transcendence and The Amazing Spider-Man 2 fell somewhere in between.

But the real surprise came 6 months later, when Barnett and Cerf looked at how those same films performed at the Box Office.

As it turns out, the ability of a trailer to put viewers on “the same wavelength” was highly predictive of Box Office success. Barnett and Cerf found that the strength of the Cross-Brain Correlation correlated with ticket sales with an R value of .68, beating out both implicit memorability measures like free recall of trailers (R = .56) and explicit self report measures like subjective rating of the trailer (R = .43) and Willingness-to-Pay values (R = .02).

These results suggest that producing similar brainwaves across viewers makes for a successful trailer. And it makes sense: if the trailer is really engaging, we’re all glued to the screen, totally captivated by what we’re seeing. On the other hand, for trailers that aren’t so good we tune out, allowing our minds to float off in their own idiosyncratic directions.

So we’ve learned that that creating similar experiences across viewers predicts success.

OK, how do we actually do that?

WHAT MAKES TRAILERS SUCCESSFUL?

Barnett and Moran have a few more findings to share about the do’s and don’ts for increasing neural synchrony in your trailer, all based on neuroscience:

Semantic complexity decreases neural similarity.

According Barnett and Cerf’s results, Hollywood should take some advice from the Navy and Keep It Simple, Stupid. The authors found that trailers with 1) more words, 2) more complex words, and 3) more unique words (i.e. less repetition) tended to have lower CBC measures. How much dialogue is in your trailer? And how complex is that dialogue? If you can tone it down, you’re likely to do better at the Box Office.

Visual complexity decreases neural similarity.

A similar effect was found for visual complexity: trailers with higher visual complexity tended to have lower CBC scores. This finding also makes sense: When there’s too much going on at the screen at once, it can be difficult to know what to focus on, leading to confusion. While some visual excitement is important to keep viewers engaged, too much of it and you run the risk of losing them.

First impressions count!

Barnett and Cerf also looked at the time periods within trailers where CBC values were most predictive of ticket sales (i.e. when is it most important to make sure everyone is on the same wavelength?). They found that the time period between 16 and 21 seconds into the trailer were the most critical, which often coincided with when the first whole sentence was completed. So don’t blow that opening line!

WHAT DOES THIS ALL MEAN FOR MARKETERS?

Movie trailers are important marketing tools: 55.9% of moviegoers report that trailers influence their ticket purchase more than many other factor (Barnett, White, & Cerf, 2016). So making sure your trailer nails it can be a multi-million dollar decision.

How do you tell if you’re hitting the mark?

Cross-Brain Correlation predicted movie ticket sales better than any of the other measures typically in the market researcher’s arsenal.

It seems like it pays — literally — to listen to the brain.